A report on the Prabérians

published in Prabérians by Thomas Rousset - Loose Joints (2022)

~2000 words

“Inside the playground an absolute and peculiar order reigns.”

- Johan Huizinga (1938)

Introduction

Over the last twelve or so years, while the rest of us were going about our lives, Prabért has gradually been forming, like a heavy bank of cloud, above an area of Alpine France known as Prabert, close to the Swiss border, fifteen kilometres north-east of Grenoble.

Thomas Rousset is the only person who we know for sure has been to this place, the only person so far to bring back proof of its existence. In the interest of transparency, and as insurance against any future scandal or inquiry, I should add here now that I have never met Rousset in person, that I was contracted to produce this report via an intermediary (his publisher Loose Joints), and that the only indication I have of his existence are two short emails in French, the first from November 2021, describing the work he would like me to undertake, and the second, from some months later, inviting me to visit Prabert/Prabért.

Shortly after I received the first message and agreed to be involved in the project, a slim package of printed images arrived at my home (also my office) in London. (The return address for Rousset was listed as an apartment building in the suburbs of Lausanne, Switzerland. The post mark however, I noted, was from France.)

The request from Thomas Rousset was simple: could we produce a report to accompany his images to give the reader a general idea of the habits, customs, morals, economic activities, emotions, diet, etc. of the Prabérians?

I’m a freelance journalist (and occasional private investigator) unaccustomed to writing the kind of rigorous, academic, well-structured, ethnographic, official ‘report’ that Thomas is looking for. I’m not sure how or why he selected me. But work is work.

And despite the obvious conflict of interest (that I am being paid by Rousset), I’d like to say now that my fidelity lies not with him (if he exists) but with the truth, with presenting a fair description of Prabért to those interested, as we are, in learning more about this relatively new — or at least until now under-described — society.

Employment

It’s unclear how the people of Prabért live. (How they make money.)

For food they clearly rely on the land, a brownish, sodden, chilly, fertile, overgrown terrain that sustains wild boars, domesticated fowl, and other farm animals such as sheep and cows. Also grains.

How Prabért links to the wider economic landscape within which it probably sits will be the topic of a later work; for now I can simply note that the presence of magazines, as well as certain other items such as newspapers, postcards, and plastic watercraft indicate not only the use of a standardised currency for long-distance trade, but also a level of connection to wider networks of commerce — postal systems, publicly maintained highways, telecommunications.

Whether there is widespread phone signal or public Wi-Fi I honestly couldn’t say, though the former seems likely.

Jobs that might exist in Prabért, to a reasonable degree of certainty: childminder; hunter; mechanic; refuse manager; photographer; photographer’s assistant; animal husbandry associate; forestry agent; miner; milliner; taxidermist; palaeontologist; lookout; launderer; lepidopterary welfare officer; falconry operative; scare-crow; personal trainer; spray tan technician; water-bearer; cook; scout; curer of meats; thresher, harvester, and other agricultural titles; interior designer; architect; taxi driver, and person who, with big combs attached to his or her hands, strokes cows.

Games

I was invited to visit Prabert by Rousset last spring, as part of the research for this report. The idea, his email explained, was that from there I might be able to view Prabért, if I was lucky, ‘much in the same way that France is sometimes visible from the coast of England on a clear day’. I took the Eurostar from London to Paris, changing stations in that city in order to take the TGV directly to Grenoble — overall a journey of less than seven hours, and very comfortable.

My expectation was that I would be hosted by Rousset himself; instead I was greeted at the station by a man, younger than I had expected, who introduced himself as Karl. He told me that Rousset had been called back to Lausanne at the last minute, on urgent business, but had made arrangements for Karl to take me on a small tour of some of the areas in and around Prabert where it was most likely that Prabért could be seen.

Slightly disappointed not to be meeting Rousset — and thinking for a brief, mad, moment that maybe Karl was Rousset playing a game, testing me in some way — I thanked the young man Karl/Rousset and followed him to the car, a beat up four-wheel-drive Subaru with five immature tomato plants in a cardboard box on the back seat and an overflowing ashtray up front between the driver’s and passenger’s seats.

We quickly exited the motorway that runs the length of the populous valley between the Chartreuse massif and Belledonne chain and began to follow winding switchbacks up into the mountains. As we ascended I questioned Karl about Prabért, concerned, if I’m honest, about the paucity of available information on the place and the effect that this might have on the quality of my report.

I wanted to know, too, if I would be able to meet any of the Prabérians, whose photographs I had studied intensively in London over the winter. After all, this report was ultimately to be about them, not just the landscapes they lived among or the economic activities they involved themselves in, the objects they crafted. I was keen to interview the Prabérians, or even just to talk to them about what it was like to live the kind of life inscribed by the subtle, interior, acquisitive images that they had created with Rousset.

I was curious about the photographer’s role in all of this as well; had he been the ringleader or merely the facilitator? Or (as I dimly suspected) simply a useful fiction, an absent centre around which the project could plausibly take shape for the outside world, like Subcomandante Marcos or Prince William?

Karl was evasive — a strange kind of smile played around his lips that I didn’t like, similar to the smile that adults might wear as they discuss Father Christmas around a child. He hoped that I would be able to meet the Prabérians, he said, staring ahead at the road. We really would try to find a few of them this afternoon. When I asked if he had met the Prabérians, he said that it would be strange if he hadn’t, living as he did in Prabert. I considered his answer in awkward silence, noting his pronunciation, a subtle one to English ears, as we drove on.

Vehicles

A manufactured object is the product of the person who put it together, but it is also an expression of the larger society within which it exists, of the community that regarded it as possible, as desirable. One object that is important in Prabért is the vehicle.

Being a rural people, Prabérians rely on a number of different types of vehicles to get around and to carry out the various tasks that presumably come with living off the land. However, a striking element of life in Prabért is the presence of vehicles for which there is no satisfactory practical reason to be found at all. Two tyres do not a horse make — and neither can a saddle be used as a tractor. Babies don’t drive motorcycles. Cars are on fire.

Why should this be so? Probably, over the course of a long period of sedimentation, play, and reorganisation, the idea of the vehicle has become important to the Prabérians, has detached from the thing and taken on its own life, later to return in a physical form quite different and strange. This can happen. Sometimes the pursuit of utility, the adaptation and remixing of something to keep it bound to a particular purpose, can produce over time a paradoxical kind of inutility, a pleasure in variation itself.

Mirrors

Unless you count the blank TV screen, the silver whiteness of the light reflectors, the ambiguous status of windows at night, and the photographs themselves, there are no mirrors in Prabért as far as I can tell.

This is not to say that appearance, display, personal grooming, etc. is not important in this place.

Games (ii)

We continued up the mountain, the car lurching and creaking on its soft suspension as we tacked back and forth around corners. A pockmarked green apple, some French cooking variety unknown to me, rolled across the dashboard, left to right then back again.

Karl’s self-consciously ‘mysterious’ behaviour, as well as irritating me, ignited a kind of insecurity within my racing mind that felt both familiar and specific to this situation. It could perhaps be summed up with the question: why am I here? This sense that I was in the wrong situation made it hard to forcefully challenge Karl, to demand clarity. Other aspects of our conversation also left me feeling tense and slightly wounded — for example, he enquired as to whether qualifications are needed in the U.K. to practice as a freelance journalist; when I told him they are not, he turned his eyes from the road, looked me up and down, and said, ‘so anyone can do it?’ I am not thin-skinned, but this seemed to me gratuitous.

We crested a wave of foothills and entered the network of raised, heavily wooded valleys within which, it is said, Prabért arose. Karl’s demeanour brightened, and he explained that we were nearing the areas, marked out on a map, where Rousset had frequently sighted Prabért through his camera lens. He said that the weather — overcast, drizzly — was perfect. Despite my anxiety, it was gratifying to feel like I was close to glimpsing the physical reality of a world that had, over the course of a long winter, seemed only virtual, isolated, hedged round, hallowed — a place dedicated to the performance of an act apart, its rules somewhat obscure to me. Now I might be able to puzzle out its order from within.

My hopes did not die swiftly — they were gradually crushed over the course of a long, wet afternoon with Karl.

We drove through cramped valleys, stopping in various hamlets, detouring down long, bumpy forest roads, making U-turns often. Karl frequently checked Google Maps and made faintly ironic sounds of confusion. Sometimes we exited the car and walked through the rain for twenty or thirty minutes, Karl studying the environment with roving eyes like an architect assessing the possibilities of a space. When I asked him what he was looking for he said, as though it were obvious, Prabért.

For my part, even as the hours wore on and my attention unravelled, I felt every now and then a little stab of elated recognition — a certain arrangement of trees, the knowing smile of a woman who looked us over as she exited a small hardware store, a derelict tractor at the side of a field. But on returning to the car to thumb through the by now well-worn package of images that Rousset had sent me in December, I couldn’t definitively locate any of these phenomena within Prabért. The woman was different, the tractor was made of hay, the trees were not right at all.

It began to get dark. We were driving again, and the forest on either side of the road became black beyond the headlights. The little lights of isolated settlements blinked on and off between the trees, warm yellows and pinky reds. I was tired, damp, dispirited. When Karl said, with a theatrical sigh, that it was unlikely we would see Prabért now, at this time of night, I was secretly a little relieved.

He dropped me back at the station in Grenoble just before midnight without the hint of an offer of hospitality. My return ticket was for the next morning. The Novotel was full, but I was able to find a room at the 3-star Hôtel Europole around the corner. I noted wearily, not for the first time in my professional life, that I had failed to negotiate expenses in my contract, and that the charge for the room would come out of my fee.

But the next afternoon, by the time I was on the TGV heading back toward Paris, my mood had lifted.

The trip had been a failure in the sense that I had not located any information about Prabért that could be of use to future scholars, but I found myself looking back on mine and Karl’s runaround the day before with a kind of equanimity. My frustrations now seemed a little over-serious, a little self-absorbed, as did my obsession with fact-finding, most likely stemming from a nervy desire not to disappoint Rousset, to produce the kind of ‘report’ that I thought he wanted.

As my mind wandered, in a ritual now familiar to me, habitual and almost hypnotic, I reached for the package of images and began again to pick through them in sequence, one after the other — looking for what, I’m not now sure.

Sublimation

It seems like it rains a lot in Prabért. I think it is fair to say that the clouds roll off the great flat plains of France, towards the foothills, and as they rise, they precipitate. On the other side of the Prabért lie the grand Alpine glaciers, which also contribute water vapour to the microclimate through a process of sublimation.

Sublimation. In chemistry: ‘the transition of a substance directly from the solid to the gas state, without passing through the liquid state.’ In psychology: ‘a mature type of defense mechanism, in which socially unacceptable impulses or idealizations are transformed into socially acceptable actions or behaviour’ (Wikipedia).

It is said that if you spend your whole life somewhere, on and off, as Rousset and the Praberians have done in Prabert, then nebulous ideas about that place unavoidably begin to form — they drift directly off you in a process of sublimation.

Prabért, looked at from a strictly scientific and/or rational viewpoint, seems to me to be the natural precipitation of this process of sublimation arising out of Prabert — not just in the individual cipher of Rousset but, I would hazard, of the entire community. (A book, like a vehicle, is also an object.)

Conclusion

I’ve never seen Prabért with my own eyes, but please don’t feel this undermines the authority of my report. The world is full of very important proclamations of great consequence being made on the basis of very little solid information or experience at all, daily, hourly. Still, our planet turns and the future stretches off untroubled into the distance.

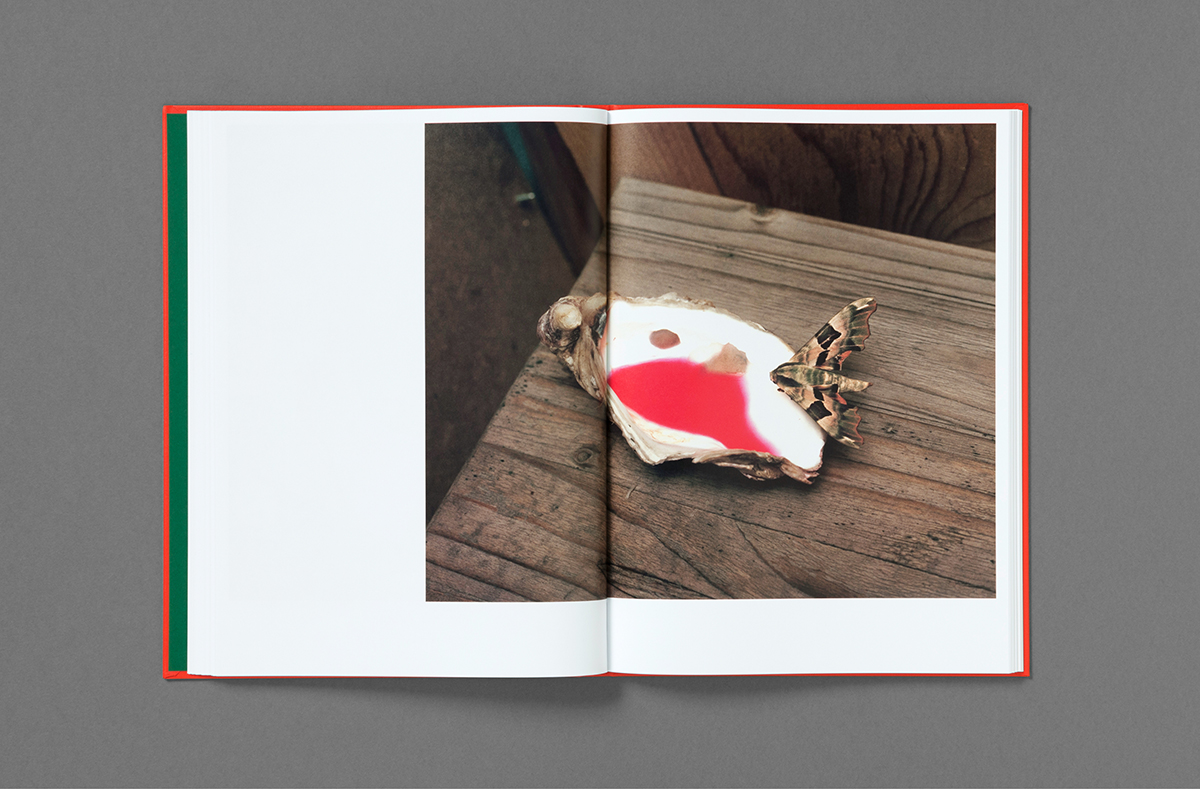

This much is true: in these images, and in the latent connections between them, lies all the material necessary to reconstruct the Prabérian world, the hopes and fears that animate it, the promises it makes. All we have to do is study the pictures, like a pack of shuffled cards, and let our conclusions float out from between the gaps.